The story of how Ion Barladeanu, the Romanian collage artist and pseudo film director, went from down and out in Bucharest to world famous

Words by LUCY NURNBERG

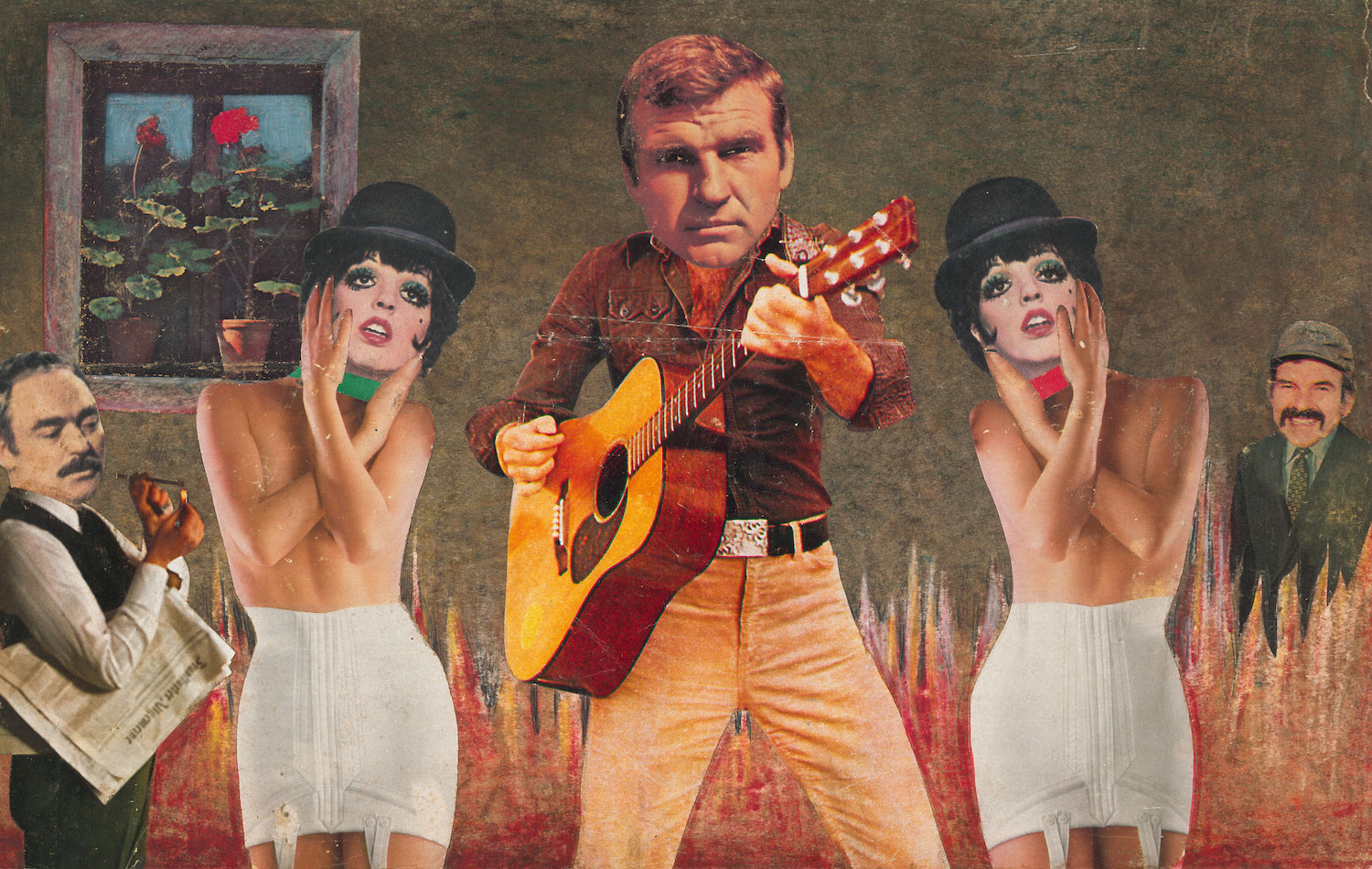

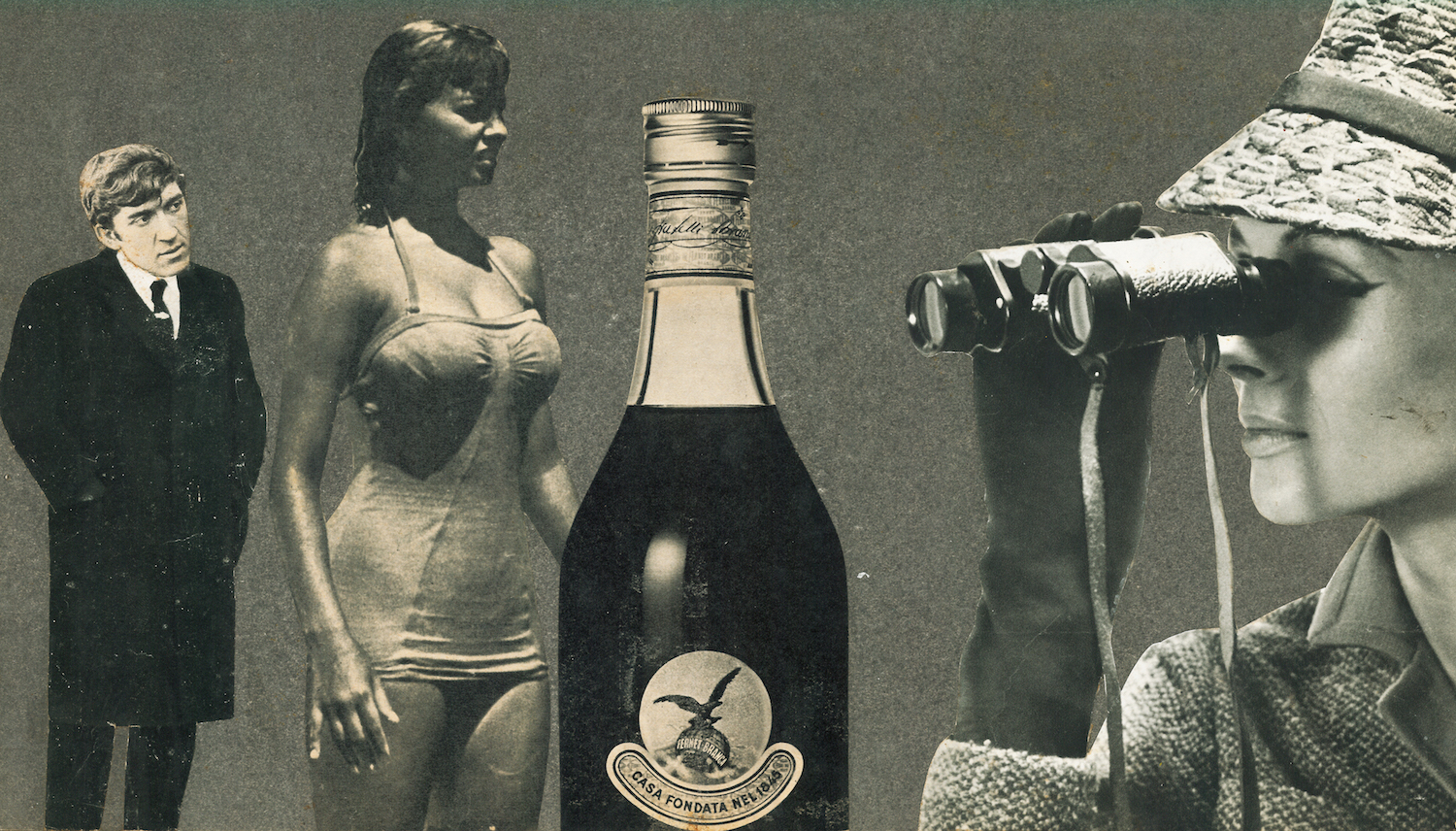

The first thing to know about Ion Barladeanu’s eye-popping collages is that they are actually film stills. Assembled in widescreen, his scenes of spaghetti westerns, spy thrillers and war epics star legends of the silver screen (Roger Moore, Sophia Loren and Brigitte Bardot among them) alongside the corrupt politicians of communist-era Romania.

Ion began cutting and pasting his cinema-inspired collages in the 1970s, when Romania was under the oppressive rule of Nicolae Ceaușescu. He worked on them in secret; the satirical content was so radically subversive that if the authorities had discovered them, he could have been landed in prison. Years later, following the overthrow of Ceaușescu in 1989 and the dawn of a new capitalist era, Ion became homeless. It was only in 2007, after a lucky twist of fate brought his work to the attention of a local gallery owner, that Ion’s surrealist artworks finally became public. His rise from obscurity to art stardom happened almost overnight.

Ion grew up in Zapodeni, a rural region of Romania that is close to Moldova. “He has a very strong, very Moldovan, sense of humour,” his curator, Dan Popescu, tells me. “That’s where the dada in his work comes from.” Ion’s father was a member of the agricultura nomenklatura in the region, overseeing the production on the state-owned land. But Ion didn’t like his father, and he left home for Bucharest at 18, making a living doing the jobs no one else wanted.

“He had a lifestyle like Charles Bukowski,” says Dan. Ion worked in turn as a dockworker, a stonecutter and a gravedigger — “he did all the work in the world” — refusing to take part in the socialist workforce. He sometimes worked illegally on the black market; at one point in the early 1980s he was caught working as an undertaker with no papers, and spent three months in jail.

In the late 1970s, Ion began making collages, without any understanding of the history of the medium. For many years he had been developing his drawing technique, and eventually he began supplementing these illustrations with photomontages created from magazine cuttings. “I’d cut out Florin Piersic, Alain Delon and Sophia Loren,” Ion remembers. “Having so many issues of Cinéma magazine, I first made a caricature, then started putting hats on the characters. Afterwards, I cut out [the Romanian actor] Mircea Albulescu’s head. I tried to see how he would look as president of Romania. It was too funny, the tricolor flag, with Nicolae Ceausescu’s club…”

Ion was completely obsessed with movies. During the communist era, cinema was a form of escape; a window on a free world. He went to the cinema regularly, often two or three times a week. He dreamed of being a director and began creating cut-and-paste scenes, using magazine clippings to cast big-name actors alongside the country’s corrupt politicians.

Ion sourced his materials from contraband magazines, mostly French, bought on the black market or found in rubbish dumps. “That’s how it was under socialism, when the comrade Nicolae Ceaușescu was the country’s prince. Then he tore down buildings and I would find pictures in basements, underground. You can still find them lying around, even nowadays. They throw them away in those huge bins that say paper, metal, iron, bottles.”

The ephemeral nature of the medium was not lost on Ion: “I’ve already got 500 kg of waste material. When I’m dead, they will all end up in the landfill. I’m only sorry I couldn’t make a school for collage-makers. Teach them how to cut out. It’s very easy.”

In his early works Ion pasted his actors and objects over hand-drawn backgrounds of living rooms, beaches or street scenes. His technique developed rapidly around 1985, when he began selecting backgrounds from magazine pages or calendars. This method enabled him to fully realise his cinematic scenes, but presented a new set of challenges. As Dan explains: “When you have a background that helps differentiate the light, the chromatics and the shades… it’s much more difficult to integrate the persons or the objects than if you make the background yourself.” Where Ion’s early works were grotesque, with a focus on the surreal characters and objects in the foreground, later works are conceived with a far greater sense of reality.

One of the things that makes Ion unique in collage is his meticulous eye for lighting; in a single composition subjects are lit from a single angle, just as on an authentic film set. And having never seen work by other artists of the medium, Ion broke many of the accepted rules of collage.

“There is a specific style Ion used,” Dan says. “Other artists work in a very modernist, flat way. There’s no depth and only a single layer. Ion didn’t know about the history of collage or the professional, academic way to make them. He needed layers to create his movies, so that’s why you see two or three layers and depth. It’s funny him not knowing it was taboo. He just did it, and something spectacular came out of it.”

As a pseudo director, Ion found the selecting of disparate parts was the biggest challenge in creating a scene: “If you’re a director, you have to place your actors in the foreground, space them apart, throw in a helicopter here, a plane there, an Obama kissing his Obama-lass.” An aside: “He was an OK president.”

In 1989, after the revolution, Ion had nowhere to go. Dan explains: “If you had been living in a flat in communist times, you were given the opportunity to buy it. But Ion was in and out of work, and he was drinking. It wasn’t possible for him. And the guys that were living in that block of flats, they took advantage of this and threw him out.” Without anywhere to live, Ion stopped making collages altogether.

He was without a fixed address for more than a decade. He survived on the streets for six years, before taking refuge in a room (with electricity, but no heating) in the basement of a Bucharest apartment block, near the communal bins. Here, in 2007, he was discovered by Ovidiu Feneș, an artist represented by Dan Popescu’s H’art Gallery. “This artist made three-dimensional assemblages and he was always going to places where they discard objects to collect items for his work,” Dan says. “He found Ion there, living in the building courtyard, with his artwork hidden away in suitcases.

“It was a Saturday on December 1, Romania’s national day, and Ovidiu came to me and said, ‘You have to come and see this guy, he’s amazing.’ ” Dan followed him and stayed for three hours. He knew he had discovered someone extraordinary.

“I was like a patron. The idea that he isn’t even self-aware of what he is doing, but everything is in place. It’s the perfect proof that art can exist anywhere, even without a very focused or rational intentionality. Sometimes it happens in a man — he just needs a little focus and a certain obsession. And it doesn’t need all sorts of means, just scissors and glue and some magazines.”

The next day, having made a discovery he knew would be the most significant of his career, Dan returned to his gallery to find there was a major problem with the plumbing. “I was sitting there and, all of a sudden, shit began coming out of the sink.” Something was blocking the pipes and the entire building’s waste was being diverted to his gallery on the ground floor. As it was a Sunday, the day after a national holiday, no one was working. “I phoned the plumbers and they said, ‘OK, we are coming, but first thing tomorrow.’ So I had to take buckets and buckets of the building’s waste out of the bathroom. And the only thing keeping me going was the thought that, OK, there’s a balance in the world — you discovered this guy, but to qualify, somehow, you have to pass through all the shit and piss and garbage that he passed in his whole life, in the course of a single day.”

It took three weeks for Dan to convince Ion to sign with him, but eventually the artist agreed that they should put on an exhibition together. A film-maker documented the process in the 2009 movie The World According to Ion B. “The first exhibition was madness,” Dan recalls. “The art scene in Romania at the time was very elitist. You couldn’t be an outsider. I had a hard time convincing people it would work, but it was very popular in the end. It’s because he’s very charismatic, he makes people laugh. And in Romania we think we are the world champions of humour.”

Within six months of the first show, Ion had a new flat and a set of dentures. He has since held shows in galleries and art fairs across Europe — from London to Helsinki — and gained countless fans. Among them is the actress Angelina Jolie; they once had lunch together in Paris, an experience he described as disappointing. “She is not my favourite actress, as everyone says. I’ve gotten so fed up with that.”

Ion is present at every opening, wherever they are in the world. “That’s one of his biggest things,” Dan says. “If you look at his collages, almost every one has a plane in it. The plane signifies freedom. In communist times, it was the idea of getting away.”

Ion’s art, and the incredible story of his rise to fame, has elevated him to a cult figure in Romania. “Not a day passes I don’t get recognised in the street,” he says. “Even if I dress up as a hobo, people still know me. And I’m proud of it.” He has found his newfound celebrity a source of amusement, although it is not without its challenges: “I went from pauper to prince. I mean, in my own field. Some things have changed, but I’ve also got plenty on my mind. It’s not good to be famous. I’m proud I don’t need a bodyguard, as the likes of Brad Pitt do. On the other hand, I could use a bodyguard, because there’s always some dumbass around.”

For the most part, Ion enjoys the merits of fame. He recalls one of his proudest moments, at an exhibition opening in Slovakia: “I tell everyone this: when I was in Bratislava with Dan Popescu, I had the biggest fame, world fame almost. I had a show in the open and I didn’t get intimidated. I spoke to them in Slovak, I told them ‘hello’ in their mother tongue. And I was surprised that there were 50, 60 people taking photos of me at one time. Men and women. Everybody. It’s amazing I didn’t go blind from the cameras flashing.”

Translations by FLAVIA YASIN; art commentary by GABRIELLA SONABEND at THE GALLERY OF EVERYTHING; portrait by ALEXANDRU PAUL; tiny cowboys by CARMEN LIDIA VIDU from the series ION BARLADEANU, MY COWBOY